The following is an overview from my first ‘Thinking Photography’ seminar on the history of photography, specifically its underpinnings in the 18th century and how it all began...

A cultural movement known as the Enlightenment or Age of Reason (1650-1800), brought about an era where acceptance of the way the world worked was questioned and challenged. In particular this meant challenging the church, specifically Catholicism. This era was responsible for paving the way for the practice we now call photography.

A pioneering group of philosophical thinkers - the likes of John Locke (1632-1704), Isaac Newton (1643-1727) and Voltaire (1694 - 1778) helped instigate this Movement in seeking to question what had previously been accepted as ‘gospel’ from the church. Instead they applied a rationale to the workings of the world. The Greeks were thought to be among the first to adopt this view and were said to have coined the term ‘philosophy’, meaning 'love of wisdom.' Prior to this period, mere superstition and religious beliefs had been the explanation for all things.

This pursuit of wisdom based on the belief of rational thinking and logic led to the beginnings of experimentation and a yearning for evidence and empiricism. Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797), an English painter began examining the effects of light and dark in his paintings. He also began to express the discussions and findings from the Lunar Society meetings (a gathering of prominent scientists, industrialists and philosophers) of which he was a member, in his works.

A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (circa 1764 - 1766) depicts a lesson on the solar system – the orrery was a device

used by early lecturers on the subject to demonstrate the planets orbiting the

sun. The light was said to be a metaphor for knowledge, awareness and ideas.

This is perhaps where the notion of ‘a light bulb moment!’ originates. Interestingly

it is assumed the term ‘philosopher’ is equal to that of ‘teacher’. This would

further support the idea that philosophers fulfilled this role and were

fundamental in the leaps forward made in this period. Not just scientifically

but also in law and music. A search for evidence, observation and proof begged

the question as to what was central to all these practices. Hence the term the

Age of Reason.

Another example of Joseph Wright of Derby’s championing of scientific exploration can be seen in An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768). This was said to be recreating an experiment by Robert Boyle who is thought to have used a number of different animals in this same experiment – early examples of empiricism and man asserting his search for answers.

|

| Joseph Wright Of Derby, A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (c.1764 - 1766) |

Photography began in an era of Classicism – its roots in ancient Greek and Roman times encompassing, literature, art, architecture (Georgian at this time echoed in its lines of symmetry, balance and proportion) and music. Classical music began in approximately 1750. A symphony written by Joseph Hayden in 1761 called Le Matin is said to be a metaphor for The Enlightenment – an awakening that starts slowly at first then builds momentum. Mozart, Bach, Beethoven and Shubert went on to bring classical music to the fore.

The camera obscura meaning ‘dark’ (obscura) ‘room’ (camera) in Latin, was in its first form, a small hole in the wall of a dark room or tent that allowed light to pass through and reflect an inverted image on a white surface on the opposing wall. This method is thought to have been first used more than a thousand years ago. This early example (below) was built in 1544 by the Dutch scientist, astronomer and mathematician, Reinerus Gemma-Frisius, to view an eclipse.The circle on the

left is intended show the sun reflecting light through a pin-hole which in turn projected an image onto a wall.

|

| camera obscura |

In

a book written by Athanasius Kircher The Great Art of Light and Shadow by the

Jesuit (1646),

an illustration depicts a camera obscura being used by an artist in the Netherlands.

A portable dark room consisting of a darkened box with a hole in the centre of

the wall either side, and a further box within.

Artists

became frustrated by the inability to capture perspective in a composition,

particularly when painting landscapes and cities. The early camera obscura

allowed artists to portray an accurate representation by enabling them to trace

the image being projected. Images were initially inverted and upside down but perspective

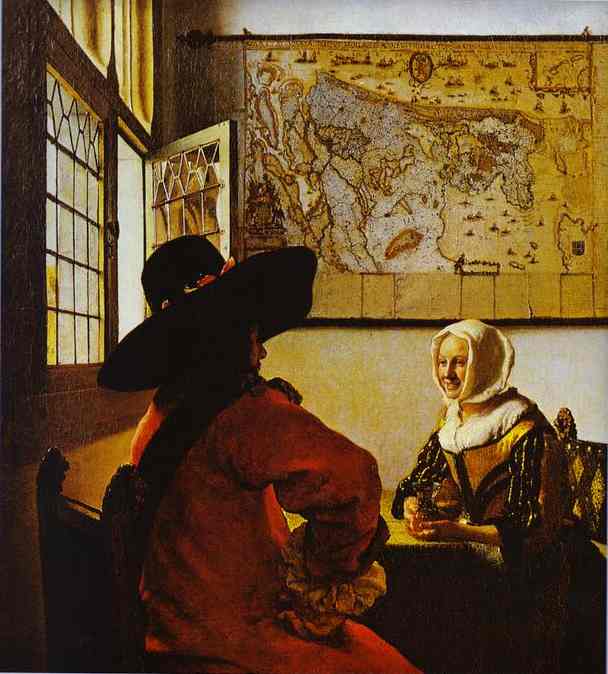

was maintained. Jan

Vermeer (1632-1675) is thought to have used a portable

camera obscura to great effect to create his paintings that replicated life

like scenes with accurate proportions and perspective. His work appeared very much like a photograph

would have. Other artists

such as Canaletto began to see the benefits of the camera obscura in being able

to replicate a scene in this way.

Perspective

was a phenomenon that came to light during the Renaissance period. The

Enlightenment (or Age of Reason) therefore understood this concept but the

camera obscurer was able to further prove the theory. The lens came to be seen

as representing fact, a purveyor of truth and could be relied upon to produce

photo-like imagery. Prior to The Enlightenment a lot of experimentation with

lenses and chemicals had began. Johannes Lipershey (1570 -1619) had already invented the

telescope in 1608 which was fundamental to the invention of the camera.

In

1769 Georg Brander, created the first table top camera obscura. Bellows were

attached to weight it so that focus could be maintained on the subject matter

in the distance. Light would bounce off a mirror angled at 45 degrees,

projecting the images onto paper which would then be traced.

|

| Table top Camera Obscura |

Arabic

alchemists (chemists) were acknowledged prior to this period for their

developments in chemistry. They observed how silver tarnished when exposed to

light. European scientists began building on their research. In 1727 German scientist

Johannes Heinrich Schulze discovered that silver salts darkened when exposed to

the sun. In 1777 Scheele a Swedish chemist observed that silver nitrate

darkened the quickest with blue light. In 1799 Francois Chaussier read a paper

in Paris on new combinations of Sulphur and Alkalis. These developments all led

to the ability to fix an image. In 1802 Josiah Wedgewood (of the Wedgewood

family of potters) reported he had successfully produced an image on leather, embedded

using silver salts.

Joseph

Nicephore Niepce (1765 – 1833) was the first to officially fix an image with

his View from the Window at Le Gras (1826). It was a view overlooking a

courtyard framed with buildings either side at a farmhouse in France, fixed on

a piece of metal, coated with silver nitrate, exposed for approximately 8 hours

(this was decipherable on the image from the way the exposure had tracked the

sun from one side to the other). This image is said to be the earliest photograph in existence. Niepce

is said to have been introduced to Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre (1787 –

1851) by a Parisian optician whom Daguerre (inspired by the success of his revolving theatre sets) was working with to try and improve upon the clarity of the lens in the camera obscura. Daguerre was a successful set designer and had opened his own diorama (mobile theatre) in Paris. Daguerre and Niepce’s began working together initially to try and reduce the exposure time required. After Niepce died suddenly in 1833, Daguerre continued their pursuit, resulting in the Daguerreotype method.

In January 1839, Daguerre

announced his invention. Using a piece of polished copper plate, polished to a

mirror like finish, the surface was fumed with iodine and exposed to produce a

fixed image. His first image of a boulevard in France required an exposure of at least 10 minutes which meant any moving

subjects were lost. This was evidenced by the one man captured and otherwise

lack of activity during exposure in this likely bustling street scene, made

possible from the static position required while having your boots polished.

Hippolyte

Bayard’s (1807 – 1887) produced a successful positive image on paper and is

thought to have been disgruntled at being ignored by the French government who bought

and patented the ‘Daguerreotype’, making it available to the world, with the

exception of the UK (who had been at war with France until 1820). Neither was

it made available to the USA, a protector of the UK until its independence from

the Empire and other parts of Europe in 1776.

At

around the same time in the UK, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800 – 1877), a keen

amateur experimenter in the arts and sciences (a typical pastime among early

Victorian gentlemen), also a wealthy landowner, had become familiar with the Camera

Lucida. It is thought Talbot used this device during a trip to Italy on

his honeymoon. He became frustrated with

being able to replicate only a simple outline of an Italian landscape in Lake

Como and later went on to develop the Calotype Method. This involved a process

using paper soaked in sodium chloride, then in silver chloride, exposing in the

camera obscura and fixing the image in sodium chloride. Unlike Daguerre’s

invention this method produced a negative from which any number of positive

images could be made.

|

| Camera Lucida |

His

first negative was of The Latticed Window

taken at Laycock Abbey in August 1835 using a smaller version of the camera

obscura he called a ‘mouse trap’. In the four years that followed Talbot developed

the process further and upon hearing about Daguerre’s invention, he quickly

announced his Calotype Method (originally named the Talbottype)in 1839. Talbot

had also experimented with items such as lace and flowers, reflecting the Victorians

fascination with Botany, collecting and preserving. Talbot would place the item

on photo sensitive paper, place a piece of glass over the top, expose it to

light and then process. These captured images such as Flowers, Leaves and Stem (c.

1838), similar to that of a photogram, was another way of preserving.

In

1841 he obtained a patent for the process in the UK. Amateur photographers had

to pay a license fee of £4 (reduced from an original charge of £20). If you

were a professional, Talbot’s license fee was £300 per year. It is thought the

reason for his patent was to go some way in covering the many thousands of

pounds he spent over the many years he was developing this process. For this

reason the calotype wasn’t popular outside of the UK. The American’s developed

the Tin Type and the French favoured the Daguerreotype.

By

the time of Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature

(c.1844) he had begun to perfect the calotype method. The title was thought

to be a metaphor for his invention – seen as a pencil, depicting nature. Exposure

time is thought to have been between 10 and 20 minutes. Although slow it was

able to pick up a lot of detail, as seen below. The term ‘photography’ still

did not exist as a way of describing this practice.

|

| The Pencil of Nature (c.1844) |

During

this time under the reign of Queen Victoria, the British Empire was at its

height, sending people out all over the world to learn about life across the

global parts of the Empire. Facilitated

by the freedom from the church but also the popularity of associations, the

coming together in society and also publishing (a cheap and accessible way of

sharing knowledge), a photograph became increasingly seen as means of documenting

and recording – a truthful, factual representation of the world witnessed previously

only in paintings. It was one of many new significant inventions that took hold

at this time. Exotic items, animals and even people were brought back to the UK

for the purpose of documenting, categorising and collecting. These became

things everyone wanted to see, to look at, to ‘muse’ at. Thus another concept

was born, the museum.

The

term ‘Photography’ is said to have finally been coined by Sir Frederick William

Herschel (1792–1871), meaning light (photo) drawings (graphy). As

the emergence of photography took hold there was a shift in portrait painters

becoming portrait photographers, adopting the same principles of painting where

there appeared to be an order of hierarchy. The children placed at the feet of

the elders, arranged by age, or the grouping of people as would have been commonplace

in paintings. An example of this is seen in David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and

Robert Adamson’s (1821- 1848) Three Women

and Child (circa. 1845).

|

| Three Women and Child (circa. 1845) |

As

yet, photography had not developed its own language. It was not being used as a

vehicle of expression or narrative but merely a means of factual representation. Hill

and Adamson began to change that and had their sitters emulate poses depicted

in paintings. The beginnings of a photographic language started to emerge in their

photographs of the elite, the noble and of the hierarchy within the military

and the church.

The

Victorian’s emphatic moral beliefs in terms of work and purpose in society, was

again at the fore during the building trade from the 1850’s to the end of the

1900’s. This belief system in the value of work in society was later reflected

in Hill and Adamson’s work.

No comments:

Post a Comment