From

its earliest beginnings photography has presented images of the body in a less

than beautiful guise. With the Victorians infatuation for photographing the

dead and experiments around the theory of Phrenology, to photojournalism portraying

images of war and suffering.

The

likes of Diane Arbus and Cindy Sherman are artists synonymous with

photographing subjects at opposite ends of the spectrum to that which might be

deemed eye pleasing. In Cindy Sherman’s series Fashion, 1983, the artist

offers herself up as numerous high fashion models that do not typify beauty,

conventional or otherwise. I would go as far as to say some are intended to

repulse.

|

| Cindy Sherman, Fashion (1983) |

Similarly for his depiction of the lesser known rural provinces of South

Africa, Roger Ballen sought out those living on the fringes of society. Only

those that made uncomfortable viewing, the grotesque and the disturbing, made

it into his images.

| |

|

|

| Roger Ballen, Puppy Between Feet, Outland (1999) |

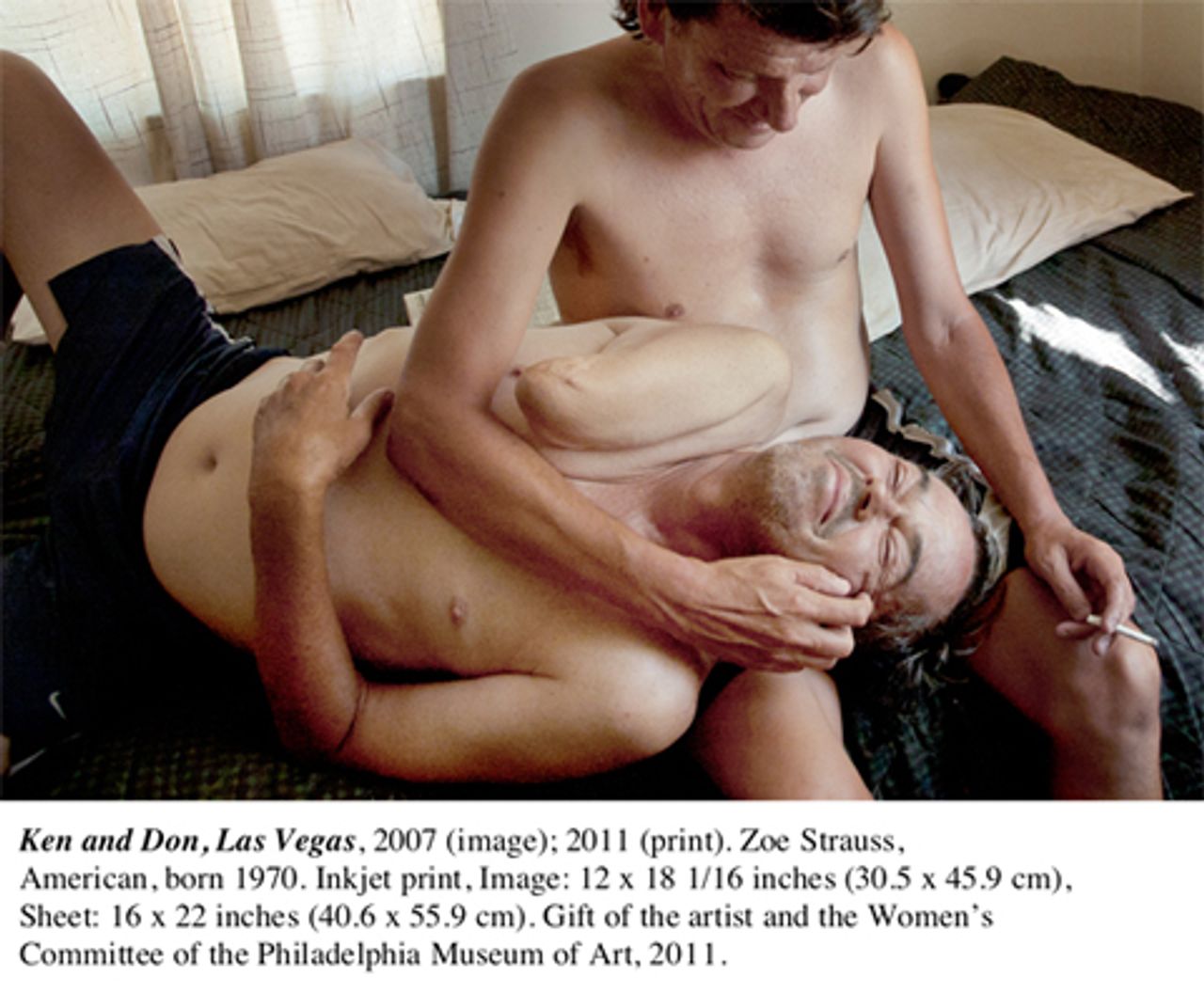

Subjects of this nature appear to be pursued for their artistic value. But there are questions surrounding them - questions of morality and motive. Professor of English and American studies, Miles Orvell addresses the delicate nature of ‘bringing ‘’art’’ to the people’ through street photography, in an accurate and fair representation of the subject without the art being at the expense of the people. In some instances, he suggests the photographer is driven by an assertion of power over the subject. He feels such images can elicit a sense of ‘them and ‘us’ and are an act of voyeurism. In Orvell’s article, THE ABSOLUTE POWER OF THE LENS: ZOE STRAUSS AND THE PROBLEM OF THE STREET PORTRAIT (Afterimage; Sep/Oct2012, Vol. 40 Issue 2, p10-13, 4), he considers the work of Strauss and artists she has been likened to. The bizarre, the stereotyped, the outcasts and those who deviate from what society deems as the norm, have all been their subjects. Orvell compares the ethos of these artists and subsequently the moral perspective from which they stand and shoot.

In the case of Zoe Strauss: 10 years, on the face of it, a relationship based

on trust has been achieved between photographer and the sitter. However, based

on the lack of knowledge the sitter has on the portrayal and future use of this

very personal image, Orvel suggests (despite numerous critics reviews to the

contrary) that is may be naivety on the part of the sitter and exploitation on

the part of the photographer. In singling out and drawing attention to the

subject’s anomalies across giant billboard posters– scars,

missing fingers, a bruised face… is Strauss’s cause(intentionally or not) only heightening them as anomalies within society and making them a talking point for our viewing pleasure?

missing fingers, a bruised face… is Strauss’s cause(intentionally or not) only heightening them as anomalies within society and making them a talking point for our viewing pleasure?

|

| Zoe Strauss, Daddy Tattoo, Philadelphia (2004) |

|

| Zoe Strauss, If you Break the Skin...( 2007) |

To further emphasise his point Orvell compares the work of Diane Arbus to Strauss. Norman Mailer, a writer and journalist is quoted as saying of Arbus, ‘Giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like putting a live grenade in the hands of a child. Troubling but always fascinating.’ (Newsweek;10/22/84, Vol. 104 Issue 16, p88).

But Strauss was it seemed, engaged and interested in her subjects beyond the decisive shot of that particular day. They were more than merely to 'facinate'. The two images above are of the same girl taken two years apart. The first, 'Daddy Tattoo' featured in Elle magazine. The girl's mother wrote to Strauss telling her of her daughters death in 2006, to thank her for taking the photograph and to tell her of her daughter's joy at being in the magazine. There is apparent exploitation but it does not appear to be on the shoulders of the photographer in this case. It is possible that in some cases, exposure and suffering is necessary or the point is lost.

In establishing his position, Orvell described Richard Avedon's In the American West (1985)to have been taken from a position of power. Avedon was 'the man with the camera', 'the master', 'the outsider'. He photographed only his subjects torso leaving the eye drawn to what he wanted the viewer to see. A detachment was made that made the photographer the voyeur.

His opinion differs on the work of Mark Morrisroe who recorded the world of Aids sufferers and prostitutes with himself as the main subject and at his most vulnerable.

| Mark Morrisoe, Self Portrait (to Brent) 1982 |

|

| Mark Morrisoe, Untitled (Self Portrait) c. 1989 |

|

| Nan Goldin, Nan One Month after being battered (1984) |

|

| Nan Goldin, Greer and Robert on the bed, NYC (1982) |

In both examples of Morrisoe and Goldin, Orvell highlights the difference - that as 'insiders'they have the privileged position of seeing the world from the subject's perspective but most significantly that from this side of the fence, the photographer is not the voyeur, we are.

No comments:

Post a Comment