Seminar 4: Modern Times – The 20th Century and Early Modernism (1900 – 1920’s)

The co-dependent

relationship between man and machine was growing ever wider. A need for human

intervention in the mechanical age was on the decline with advancements in technologies.Modernism

brought about a general rebellion of historicism. Instrumental to its school of

thought was Albert Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity (1905), addressing physics

in terms of space, time (dilation – ‘the elapsed time between two events’) and

light. It questioned science as we had known it.

Similarly Cubism

(Analytical 1907 – 1912 and Synthentic Cubism

1912 - 1919) questioned perspective as we had known it, showing it was not

definitive but variable dependent upon the angle of the observer which lead to

its three dimensional characteristics. Most closely associated with the works

of Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973), Henri

Matisse (1869 – 1954), Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968), Paul Cezanne (1839 – 1906)

and Georges Braque (1882 – 1963), it also expressed movement and considered mass, time and space. Images were expressed as if a life drawing or painting were overlaid with a further image from a different angle as you moved around the subject.

|

| Georges Braque, Violin and Candlestick, Paris, 1910 |

|

| Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907 |

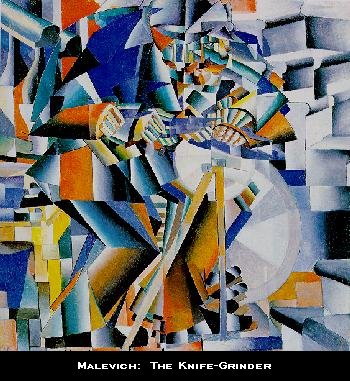

Futurism

(1909 – 1916), born out of Italy and influenced by Cubism, was an expression

and an embracing of all things new. Abstract in its interpretation, it sought

to celebrate speed, the technological age, violence and all things industrial.

They wanted no part in nature. Nature was weak, while man was all powerful.

|

Kazimir Malevich, The Knife Grinder, 1912 |

Voticism

was a British modernist movement, circa 1913 that took its lead from Cubism, favouring

geometric shapes and abstract works. World War 1 is thought to have seen the

movement run out of vigour.

Photography

had begun to gain some artistic recognition for its purpose other than just a

means to record but practitioners continued to feel the frustrations of a

medium lacking credibility as an art form.

The painterly

qualities of Pictorial Photography, championed by the Photo-Secessionists from

1902, had somewhat successfully elevated photography’s status but it still had

a long way to go to be seen equal to art. In 1905 in New York, the Little

Galleries of the Photo Secession

opened its doors to the public. The tiny gallery on 291, 5th Avenue,

the brainchild of Alfred Stieglitz (1864 – 1946) and Edward Steichen (a former

painter), saw hundreds pass through its doors in its first weeks. This gave the

Photo-Secessionists a platform to enter the media and soon their works became a

talking point and the topic for debate and discussion. Stieglitz went on to use

this notoriety to invite all manner of artists to exhibit at what later became

known simply as ‘291’. It was a collective of creative minds – not only

photographers and painters but also musicians, critics and poets who would meet

and exchange ideas. Most importantly to Stieglitz he saw this affiliation as a

way to raise the profile and status of photography.

|

| Picasso and Braque exhibition at 291 (Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession) |

In doing so he is thought

to have been instrumental in the introduction of Modern Art in the USA.

Providing a gateway into the

art world of America, artists such as Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, Paul and Duchamp

held their first exhibitions at 291.

Having first exhibited in Paris in 1901, Picasso didn’t think America would be

accepting of his cubist works and confirming his thoughts, The Metropolitan Museum

are said to have initially rejected Picasso’s pictures. Following an exhibition

at 291 in 1911, only two pieces were thought to have sold - Stieglitz being one

of the buyers, picking up the piece for between $20 - $40 dollars.

Stieglitz eventually negotiated

with the All Bright museum and secured the inclusion of photography in to their

gallery on the condition it was hung at regular intervals to other pieces of

artwork. While Pictorial photography had opened doors, by this point Stieglitz

and many others, influenced by the likes of Picasso, Cezanne and the realist philosophies

of Modernism had begun to move away from the soft lines of pictorial imagery,

in favor of much sharper images portraying life of the time.

|

| Alfred Sieglitz, The Terminal, 1892 |

Dada (1915 – 1922), were

an anti establishment group who rejected all rational thought and ideas,

thinking it was this logic that had led to WW1. Its beginnings were in

Switzerland then moving on to Berlin, Cologne, Paris and New York. Dadaism

encapsulated many forms of art including literature, photography, film,

sculpture and assemblage. In 1916, Dada established regular meetings at an

underground club in Paris’s red light district. They eventually came to an end

later the same year due to their reported excesses and wild behavior and to set up at a similar venue - Galerie Dada.

|

| Marcel Duchamp's, Fountain, 1917, replica 1964 |

Positioning

itself as almost anti art, it claimed to be against art in the traditional

sense and that which could be found in galleries, instead favoring the kind of

art they expressed at The Cabaret Voltaire and examples such as Fountain, Marcel Duchamp, 1917 (photographed by Alfred Stieglitz). Dada works were described as

being based on chance and random events and sometimes just to mock. It was highly influential on the Surrealist

movement that followed.

No comments:

Post a Comment